Chances are you’ve heard of Target Date Retirement Funds (TDRF) by now – they have blown up in popularity and size over the last several years. According to Morningstar research, TDRF funds:

- Have more than $650 Billion in assets as of March 2014 with strong growth continuing

- Are 67% actively managed

- Have an average fee of 0.84%

- Aren’t owned by their own TDF managers

TDRF’s are, in reality, a collection of underlying investments. They are designed to put your retirement investments on autopilot based on your estimated target retirement year. But how do they really work?

Selecting Investments

The fund company will offer various funds categorized by the future expected retirement date of the investors – often in 5 or 10 year increments.

For example, the TDRF 2030 fund will invest based on the assumption that all of its investors plan to retire in the year 2030.

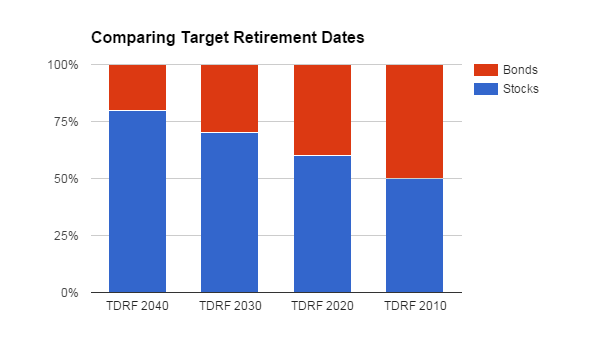

The “target asset allocation” – or categories of assets you invest in – are pre-set for each fund. The further away the target date, the more aggressively it invests. You can see this demonstrated below in our target date examples (more blue = more aggressive).

The manager then selects the underlying funds to fill each pre-defined target. For example, on the TDRF 2030 above, the manager must fill up the 70% stock bucket and 30% bond bucket with actual stocks and bonds.

Managing Investments Over Time

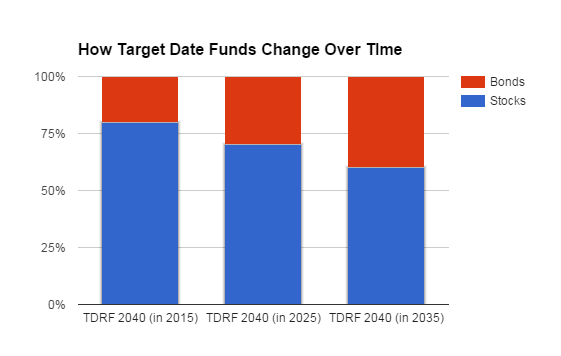

As you can see below, the target allocation changes to a more conservative allocation over time (for all TDRFs) because the length of time to retirement is decreasing. This is sometimes called the glide path. The glide path allows the fund to become more conservative without any action on behalf of the individual investor. It’s automatic.

Over time the market goes up and down and varying asset classes (like stocks and bonds) behave differently. This causes your allocation to get out of balance. Therefore, the manager must also rebalance the underlying investments back to the predefined target over time.

Important Considerations with TDRFs

Expense Ratio

Expenses are a huge driver in determining future performance – especially the non-productive expenses that have no bearing whatsoever on performance… like marketing expenses, revenue sharing, commissions, etc. For many funds, the actual management fees make up a small fraction of the actual expenses. You should understand what you’re paying!

Most TDRFs offer multiple share classes. The various share classes essentially offer the exact same underlying investment fund, but at a different cost to you. For example, The American Funds 2030 Target Date Retirement Fund offers 13 share classes! Here are all the tickers:

– AAETX – BBETX – CCETX – FAETX – FBETX – RAETX – RBETX

– RBEEX – RCETX – RDETX – RHETX – REETX – RFETX

The range of operating expenses is 0.41% on RFETX to 1.53% on RAETX – all for the same underlying investment. I would consider the difference here to be the non-productive expenses. You will not see any added return whatsoever as a result of paying the added expenses associated with RAETX. So why pay them?

As such, I would be inclined to choose RFETX if I was investing in this fund. Think that 1.12% difference is not a big deal? Well, if you invest $10k for 30 years and the underlying investment (before expenses) returns 8% annually, your net balance with RFETX will be just over $1.05 million vs. RAETX with just over $859K. That’s $191K in expenses over 30 years – that’s a house!

It’s a no brainer to cut the non-productive expense fat from your chosen TDRF in order to make them as efficient as possible.

Aside from the share class variance, it’s common to pay additional expenses for the autopilot function itself. For example, the Vanguard TDRF 2050 (VFIFX) fund has an expense ratio of 0.16%. It functions by purchasing 4 underlying Vanguard funds and rebalancing them for you. If you replicate this process on your own using the Admiral share class (requires $10K per fund), the weighted expense ratio would be 0.09%. I would look at this difference as an expense just to have it on auto-pilot… a convenience expense.

Your Current Risk Tolerance

Risk tolerance and capacity will be different for different people. This can cause problems with the TDRF. If, for example, you are much more conservative than the average person expecting to retire in 2030 (or whatever year), the TDRF will not be a good fit.

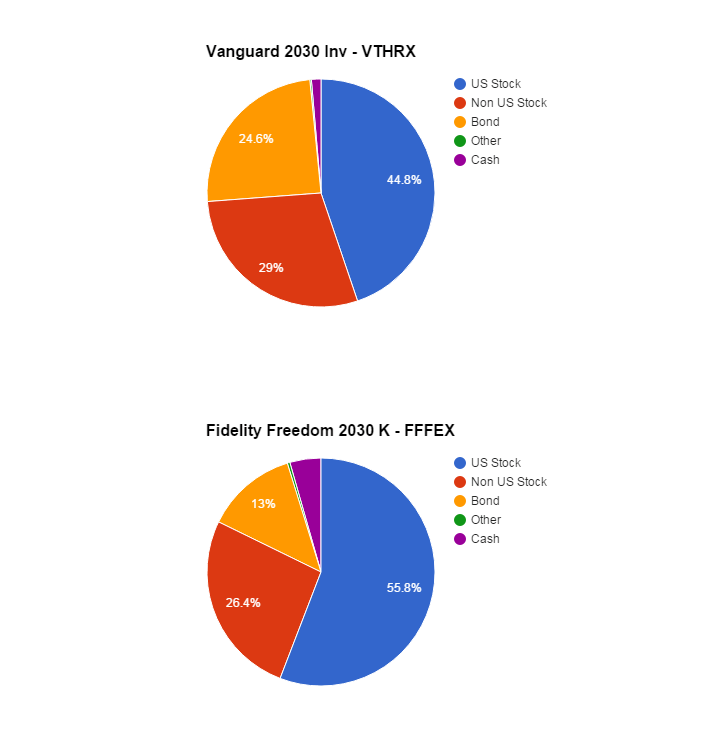

Also, different TDRFs with different fund companies have large differences in risk exposure that people may not realize. For example, in the pie charts below we compare the Morningstar allocation for the Vanguard 2030 fund and the Fidelity Freedom 2030 fund. The Vanguard fund bond holdings are more than 10%

higher.

If you compare these same two funds in 2008, you can see FFFEX returned -36.93% and VTHRX returned -32.91%. The 4.02% variance was likely due in part to the fact the Fidelity fund is taking more risk by holding less bonds.

For TRDF’s to work, the autopilot risk exposure must match your personal tolerance and capacity for risk.

Your Future Risk Tolerance

What about the TDRF’s future investment allocation? How quickly does it shift from stocks to bonds? There is a big variance between different funds. You need to make sure the fund’s “glide path” lines up with your personalized, ideal glide path.

Your Outside Investments

The TDRF is most likely to work well when it’s the only investment you own. They are built to be an auto-pilot one-stop-shop solution. But as you add different types of accounts with varying underlying investments, the TDRF approach can begin to cause inefficiencies.

What if you work at Apple and have stock options? The largest underlying asset of most TDRFs is Apple – they don’t account for you owning lots of it already. Or what if your wife’s retirement account at work has terrible options except for the US stock option… maybe it’s best for you to own 100% US stock in your wife’s plan and round out the rest of your target allocation with your retirement plan. The TDRF will not work for this customized approach.

One of the most common mistakes people make is they treat TRDF’s like any other mutual fund or ETF. In fact, I was just looking at a 401k today where the individual owned 25% in TRDF’s and the remainder in random funds. That’s typically not the best approach. It’s like opting to manage your investments yourself but then selecting an investment that’s designed for people that don’t want to manage their investments.

Active vs. Passive Management

This is a totally separate bear of a subject – you can read books upon books about it… but here is the short story. With active investing, the goal is to BEAT the market – the market being the entire collection of underlying investments you can choose from. An example market might be all stocks in the US. An active US stock fund’s goal is to pick the winners and outperform the collective market.

With passive investing, the goal is to MATCH the market. Instead of trying to pick the winners, a passive US stock fund will simply buy the entire market. The fund’s return will be the market’s return less expenses. Academic circles favor passive investing. Wall street favors active investing. I’ll save my opinions for another day.

For starters, you should have your mind made up as to whether you want to use a passive, active or combination approach. When considering the TDRF, you need to understand whether it’s active or passive. According to the Morningstar research noted above, 67% of TDRFs are active. Most educated investors I talk to today favor the passive approach, yet many of them unknowingly are using an active approach with their TDRFs.

Underlying Cash Holdings

In case you weren’t aware, cash is an inefficient long term investment vehicle. It’s very difficult to build wealth holding cash. When considering TDRFs or any investments for that matter, you should be paying attention to the fund’s cash holdings. Typically, less is more with cash inside your TDRF.

To give you an idea of the variance between funds, the Russell LifePoints 2030 fund (RRLAX) holds 10.83% cash. The Vanguard Target Retirement 2030 fund (VTHRX) holds 1.35%. That’s huge! I am not sure why Russell is holding so much cash but I would never want that much of my money sitting on the sidelines. It needs to be put to work!

Buys And Sells (aka Turnover)

It’s worth it to understand how often your TDRF is buying and selling underlying stocks and bonds – especially if the investment account holding them is taxable (like an individual brokerage account or joint investment account).

Why is this important? The more your TDRF fund buys and sells investments, the higher your tax and trading expenses. Some TDRFs have a very high volume of buying and selling (sometimes called turnover) and others are extremely low. Every buy and sell has tax consequences and trading costs for you to pay. Generally, it’s a bad idea to own TDRFs with high turnover inside taxable accounts unless you’re in a very low tax bracket.

Your Withdrawal Strategy

Quality TDRFs can work well for the average retirement scenario. But people often have unique circumstances. For instance, what if you have a deferred compensation plan that requires you withdraw the funds over a set period of time? Let’s say for instance you must draw down this plan in your first five years of retirement. If this is the case, the standard allocation is likely too aggressive for you – given your uniquely short time horizon.

The same could be true if you’re considering TDRFs in a taxable investment account which you plan to spend down in your first phase of retirement. It’s likely not going to fit the boilerplate mold of the typical TDRF.

TDRFs vs. Alternatives Available

Ultimately, one of the most important factors in considering the TDRF is: what’s the alternative? If the account is a 401k, it’s likely you are limited to a handful of choices outside the TDRF. For some 401k’s, TDRFs are the only choice. On the other hand, if you’re using an IRA, the options are almost unlimited. Let’s consider two over-generalized types of people and how they might handle TDRFs…

1) Proactive and very experienced investors (or those with advisors helping manage their investments) with large account balances and many different types of accounts: Generally, this group is better off using individual funds IF quality options exist.

2) Inexperienced investors that aren’t going to monitor investments and only have one small account: Generally, this group is better off using TDRFs as long as they are quality funds.

Ultimately, the “right” decision depends on your individual circumstances. Either way, a great starting point is learning the basics and/or hiring help. If you plan to hire help, look for someone whose livelihood is not tied to the expenses of your investments.